PROLOGUE: City Point was one of New Haven’s first planned suburban developments, bounded by Greenwich Ave., Hallock Ave. & South Water Street. It was envisioned c. 1840 by journalist Gerard Hallock, who formerly owned the land. City Point was established officially in May of 1868 by his heirs on the former (now largely land-locked) narrow peninsula or “point” once known as “Oyster Point”. This 1868 residential housing development incorporated the earlier oystering community established in 1847 when Gerard Hallock sold 2 acres of his land along the Point’s southern shore (which later became South Water St.) to William S. Barnes: the Point’s first oysterman.

CITY POINT: It’s NOT “The Hill”.

by Christopher Schaefer © copyright 2008; Revised-expanded edition © copyright 2017

Oyster Point & The Oyster Point Quarter

City Point was originally part of New Haven’s undeveloped “suburbs” on the western edge of town known as the Oyster Point Quarter or simply Oyster Point. By 1824 this was considered to be bounded on the north by what is now Columbus Ave. In 1848 a small stream in the Oyster Point Quarter was drained to create the New York & New Haven railroad cut now used by Amtrak and Metro North, and this eventually came to be regarded by some residents to be the northern boundary of Oyster Point. Nevertheless some maps as late as 1870 still show Oyster Point extending to Columbus Ave. or to the avenue’s neighboring 1870-71 Derby Rail Road cut.

The Point was bordered on the east by New Haven Harbor, which originally extended along the entire length of present-day Hallock Ave. At Lamberton and Cedar Streets, the harbor’s shoreline veered somewhat eastward along the former West Water St., extending to somewhat north of present-day Union Ave.

Oyster Point was bordered on the west by the West River salt marsh, which originally extended along much of present-day Greenwich Ave. The marsh was fed partly by a small stream originating near Kimberly Avenue, approximately behind what is now number 400 Greenwich Ave., between First and Second St.

Most of this area formed a “point” or narrow peninsula jutting out into the harbor.

Although Oyster Point and Oyster Point Quarter often were used interchangeably, most 19th century maps use the name Oyster Point to describe the narrow peninsula bounded by the West River salt marsh and the harbor., i.e. the area today bounded by Greenwich Ave., Hallock Ave. and South Water Street.

The name Oyster Point Quarter, on the other hand, usually was used to describe all of the area bordering New Haven Harbor’s original western shoreline, i.e. the area from Columbus Avenue southward.

Gerard Hallock

In the 1830s Gerard Hallock (1800-1866), a New York newspaper editor, purchased much of this land as his rural estate and in 1836 Sidney Mason stone (1803-1882) built Hallock’s summer residence overlooking the harbor on what is now the rail yard side of Cedar St., across from present-day Cassius St. This impressive “Elizabethan Gothic” mansion, modeled after Kenilworth Castle in England, sat upon a semicircular outcropping supported by a massive 2,000 foot-long sandstone wall, making an impressive sight from the harbor. It soon became a navigational reference point for ships entering the harbor. Although Hallock spent much of his time in a small apartment adjacent to his newspaper’s press room in New York, his 40 acre New Haven property soon came to be known as “Hallock’s Quarter” and the mansion “Hallock’s Castle”.

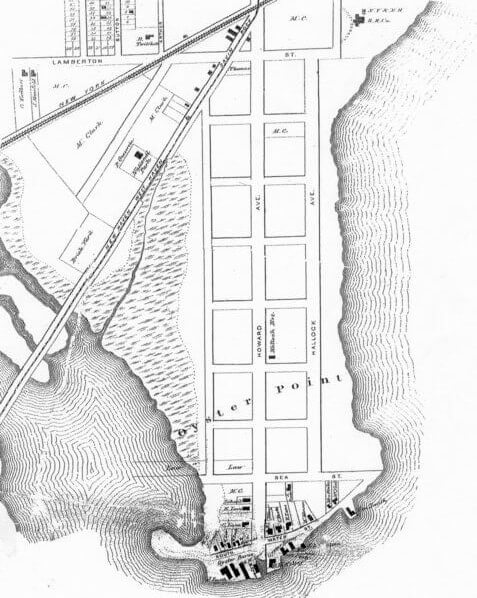

It was Hallock’s vision that his land south of Spring Street would be developed into a neighborhood of fashionable country estates. Thus, undoubtedly reflecting Hallock’s influence, in the first-ever city directory Patten’s New Haven Directory, for the Year 1840 is found a map of New Haven with a “contemplated” blueprint of Oyster Point, filled with a grid of unnamed, non-existent streets, and the name “City Point” across the area. This map of non-existent streets—on which the traditional name “Oyster Point” is completely absent—continued to be used in city directories through the 1840s.

For many years ‘Yalies’ and ‘townies’ would pass Hallock’s Cedar Street mansion on the way to The Cedars, which for over seventy-five years was a popular beach—on Hallock Ave—located approximately between the present-day intersections of Lamberton & Hallock Ave. and Second Street at Hallock Ave! Here men would swim au naturel and during the 1880s & 1890s one could rent boats and buy refreshments at the Vue de L’eau [“View of the Water”] Pavilion operated at this beach by carpenter, builder and carriage maker Godfrey Grenier at 241 Hallock Ave. near First St.

Gerard Hallock opposed slavery and used his wealth to purchase the freedom of c. 100 southern slaves. He was a devout Christian pacifist and defender of Constitutional law. Therefore he believed that “radical” abolitionism, i.e. use of coercion or northern Personal Freedom Laws (which defied the federal Fugitive Slave Act) would cause anarchy, civil war and dissolution of the Union. He insisted—rather naively, we can say today—that the “spread of the Christian Gospel” eventually would result in the end of slavery, so founded the Southern Church Aid Society. His editorials criticized the tactics of the war wing of the Republican Party and the Lincoln administration’s unwillingness to negotiate with the South after the seizure of Fort Sumpter. Those who disagreed with him falsely labelled him a “Southern sympathizer” or “pro-slavery”. Consequently, after the American Civil War broke out in 1861, the Postmaster General suspended the mail privileges of Hallock’s Journal of Commerce on the grounds of “disloyalty”. Thus, to preserve the newspaper, Hallock resigned as editor and took up permanent residence in New Haven. During the Civil War the all-Irish Ninth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers as well as the Connecticut Fifteenth Volunteers trained on land which Hallock volunteered for the purpose, approximately where Bay View Park now stands. During the war this military encampment was known as Camp English, after then-Governor James English.

Gerard Hallock died in his New Haven “castle” in 1866.

The Oyster Industry

In 1847 oyster grower William S. Barnes established his business at the southern tip of Oyster Point, on land purchased from Gerard Hallock. By 1850 he was joined by Richard W. Law, then Alexander Foote by 1854, with Eber Kelsey & Frederick Lane setting up shop by 1855. Initially shucking and packing of oysters took place in the high-cellared, beach-front homes of the oyster growers. The industry grew rapidly, so that by 1860 the original beach had been extended to accommodate a new privately-owned street—South Water Street—with the oyster-related activities now taking place in oyster barns. These were built upon additional infill on the opposite side of South Water Street. Industry-related buildings also sprang up on Sea St. Due to the industry’s rapid growth, the city drew up plans in 1872 to take over and widen South Water St., although this plan was not carried out until 1886: “The City of New Haven has taken for the definite layout of South Water Street from the Easterly line of Greenwich Avenue extended, to the Southerly line of Sea Street a strip of land sixty feet (60′) wide, or so much of said strip as was not already dedicated to the use of a street from the owners fronting on said strip” (Land Records, City of New Haven: Vol. 380, p. 471, March 3rd, 1886). The planned extension of Greenwich Ave. from Sea St. to S. Water St., referred to above and shown in the 1872 map, as well as in the 1867 map commissioned by Gerard Hallock’s heirs, never was carried out. (See Historic Maps page.)

Early in the oyster industry’s history, dugout canoes were used when tonging for oysters. Soon these were replaced by oyster boats called sharpies, a unique New Haven vessel. One-mast sharpies were used for tonging, two-mast versions for dredging. The two-mast sharpies built at Oyster Point by Riley Smith (of Smith Brothers Oyster Growers) were distinguished from the Fair Haven versions built across the harbor by their brass bow piece.

The “Great Set” (i.e. oyster spawning) of 1899 produced record oyster harvests in New Haven Harbor and Long Island Sound through 1903. Thereafter the oyster industry slowly declined due to predatory starfish, pollution, poor oyster bed management, the hurricane of 1938 and loss of workers due to World War II. Changes in currents and salinity caused by construction of harbor breakwaters in 1893 and filling of the West River salt marsh in 1929 (to create Kimberly Field) also contributed to the decline. The Nor’easter of Thanksgiving weekend in 1950 was the final blow for many oyster companies. City Point’s last oyster company, Sea Coast, closed in 1962.

City Point Mission

The history of one of City Point’s landmarks, the former Howard Avenue Methodist Church building, now home of New Light Holy Church, began in 1871 as Sunday school lessons conducted by Mrs. Gilbert Eaton in her home on South Water St. The Eaton’s initially had relocated from Long Island to Second Street in City Point, but soon moved to South Water Street. According to local legend this was at No. 47-49 South Water St., and some residents continued to call this house the former “sailors’ mission” well into the 20th century. City directories confirm that one of the several City Point Eaton families lived at 47-49 South Water St. in the 1860s-1870s. Also, according to local legend and parish archives, the first services were held in a newly-constructed oyster shop directly across the street, owned by the Thomas Oyster Co. (the building now relocated to Mystic Seaport Museum). By 1872 the group called itself “The Oyster Point Mission”, and shortly thereafter “The City Point Mission”.

In the New Haven Directory of 1875 the City Point [Methodist Episcopal] Mission on South Water St. is listed for the first time. This address likely was the parsonage, because a church building or ‘meeting house’ was constructed for the congregation by David Shelton in 1875 on a 50′ by 300′ lot which he had owned since 1872, and which was bounded by Hallock Ave., Sixth St. and Howard Ave. (The corner stone of the present edifice on Howard Ave. at Fourth St. gives this as the year of the building’s construction.)

On Oct. 19, 1880 David Shelton, for the sum of $1000, sold to the congregation “The Church or meeting House”—but not the land upon which it sat—”with the following Furniture and fixtures therein Viz: One Black Walnut Pulpit, One sofa, Fourteen Chairs, Fifty-nine settees or seats, Ten Double Lamps and about two hundred yards of Carpet on the Floor.”

On July 15, 1881 David Shelton then sold the congregation the lot at the corner of Fourth St. & Howard Ave. for $600. The 1881 City Directory gives both South Water St. and Howard Ave. at Fourth St. as the Mission’s addresses. This was the year of the building’s legendary two to three week move up Howard Ave., during which services purportedly were held while the building temporarily sat in the middle of the Avenue. In the 1882 City Directory the name then only appears in the church index as the Howard Avenue Methodist Church at Howard Ave. & Fourth St.—although the street index continues to call it City Point Mission at Howard & Fourth through 1887. Despite these official names, local residents often simply called it “Fourth Street Methodist”.

From the 1930s, until the parish merged with Grace Methodist farther up Howard Ave. in 1954 (thereby becoming Wesley Methodist), the church was well-known for its Sunday oyster suppers held during December. The oysters were donated each year by the Wedmore Oyster Co.

In 1959 the church building was sold to United Pentecostal Church, then Star of Jacob Church. It has been the home of New Light Holy Church since 1973.

A New Suburban Housing Development

One year after Hallock’s death in 1866, his heirs sold his land between the northern side of Lamberton St. and Spring St. to the New Haven & New York Rail Road. In 1874 the rail road moved his mansion across the street, to where nos. 4-16 Cedar St. now stand, and began filling in part of the harbor to build much of the present-day rail yard. Stones from his semicircular harbor front wall were used to build part of the present rail yard retaining wall.

Hallock’s land from the southern side of Lamberton St. to Sea St. was surveyed, mapped and divided into building lots by his heirs. This new housing development was bounded by new streets—Hallock Ave. and Greenwich Ave.—and new cross streets were included: First through Sixth Streets. (His heirs, being New Yorkers, naturally adopted the numbered system for naming cross streets).

Finally, a grid of streets envisioned on the map of 1840 was to become a reality.

Thus, many residents began to regard the northern boundary of this new residential neighborhood, rather than the rail road cut, to be the northern boundary of Oyster Point—soon to be renamed City Point—i.e. the southern, even-numbered side of Lamberton St. at Hallock Ave. [nos. 20-32 Lamberton], continuing over to just before the intersection of Lamberton and Kimberly Ave., and angling down the rear yards of Kimberly to Greenwich Ave. at First Street. (This approximately is the northern boundary of City Point as defined by the New Haven Preservation Trust in its 1982 publication New Haven Historic Resources Inventory.)

Thanks to the 1860 introduction of the horse-drawn streetcar (electrified in the 1890s) Kimberly Square soon developed into a commercial hub. This provided convenient shopping for nearby residents of this newly laid out Oyster Point residential neighborhood. Thus the ubiquitous “corner store”, once an essential part of urban neighborhoods, was and remains something of a rarity in City Point. A few 19th century exceptions were no. 323-25 Howard Ave. (built in 1895 as a grocery store and meat market, now Tracey Oil), 86 Second St. (built in 1871 as a grocery store, now an apartment), and 228-30 Greenwich Ave. (now a brick 2-family house).

Early 20th century additions included 382 Greenwich Ave. (now an apartment, but the original 1925 location of Eddy’s), 151 Howard Ave. (opened in 1925 as George Stavrides’ confectionary [candy store], more recently City Point Bubbles Laundromat), 99 S. Water St. (Starbranch grocery, later Libson’s), 83 S. Water St./19 Howard Ave. (Charlie Eaton’s grocery), 68-74 Second St. (now an apartment building, but for many decades the Rustic Garden Restaurant, known for its dining booths concealed by beaded curtains, allowing patrons to dine in semi-privacy), and 353 Greenwich Ave. (The New York Smoked Fish Co., destroyed by fire in 1975 and the remains eventually replaced by a 19th c. house relocated from Kimberly Ave.).

The post-Civil War economic decline and the fact that the streetcar did not continue down Howard Ave. past Kimberly Ave. slowed development of the neighborhood. The nautical chart New Haven Harbor, published in 1872 by the US Coast Survey, shows the greatest concentration of new houses in City Point is at the intersection of Greenwich Ave and Second Street. This cluster of houses was like a small village, with its own grocery store at 86-88 Second St, run by Francis “Frank” Hogan.

The 1877 United States Coast Survey map of New Haven still shows most development in City Point is near the intersection of Second St & Greenwich Ave: http://emuseum.chs.org/emuseum/objects/17636/city-and-vicinity-of-new-haven-connecticut-derived-wholly?ctx=ab6df61796b123954af4f4a79729cf13a1d99354&idx=0

The 1888 Atlas of the City of New Haven continues to show very few homes between Second and Sixth Sts. However, the return of prosperity in the 1890s and the extension of the now-electrified streetcar to the end of Howard Ave (the Q car, later the B car) resulted in a building boom, so that during this time most of the remaining building lots in the City Point neighborhood were built upon.

By the 1880s the gas main had been extended into City Point, and for many years the Ahern boys of Second Street had the job of lighting the street lamps at dusk and extinguishing them at dawn.

Bay View Park

In 1890 the city acquired land for the development of a park to be built on the edge of the harbor, between Fifth and Sea Streets. However, this purchase was not without considerable newsworthy controversy. Residents of the area—the former Fourth Ward—had petitioned the city to purchase the waterfront along the portion of Hallock Ave. from First St. to Fifth St., instead of “the Oyster Point end of the Cedars” below Fifth St. They argued that the upper portion of the Hallock Ave. shoreline already long had been used as a recreational beach—The Cedars—“where we have been in the habit of going and our fathers and mothers for the past sixty years or more” and would be more convenient to a larger number of residents. The upper location also would provide more water frontage and would be farther from the noxious sewage outlet located at Sea & South Water Sts. The many petitioners also noted that two-thirds of the parcel being considered south of Fifth St. was covered by mosquito-infested water at each high tide and therefore would require construction of a sea wall, then back-filled to develop the park—at considerable expense. Petitioners also claimed that this lower area was being favored by the Park Commission solely because it was owned by the Fourth Ward’s influential Alderman Foote, who wanted to “unload” his undesirable “potato patch” to “feather his own nest”.

However in April of 1890 Attorney Pigott had pointed out to the Park Commission that a portion of the Hallock Ave. shore near Lamberton Street now belonged to the Consolidated Rail Road “and the supreme court decided two years ago that railroads could condemn city land, even streets, for railroad use.” Therefore, if that upper portion of Hallock Ave’s shore was purchased from the railroad and made into a park, the railroad could condemn it at any time in the future and return it to railroad use.

Thus, despite its drawbacks, the lower plot—bounded by Fifth St, Howard Ave, and Sea St—was purchased by the city in late 1890 for $60,000. Ironically, the land already had been offered to the city—as a gift—many years earlier, from then-owner Gerard Hallock, specifically to develop a park. However, the city declined the gift at that time—“because there would be some expense for new streets”.

Ultimately, the new park was championed by George Dudley Seymour (known as “Mr. New Haven”), a proponent of the City Beautiful movement, and its design was developed by landscape architect Donald Grant Mitchell. Mitchell’s 1891 plan dubbed the park Oyster Point Reservation, but by 1892 the name had been changed to Bay View Park. By 1894 it included a central duck pond (actually a tidal basin) with two picturesque rustic bridges leading to a small island, and a tree-lined harbor drive (built upon soil excavated to create the tidal basin and held in place by a wooden bulkhead). Although the duck pond consisted of a single body of water, residents referred to the halves bisected by the island and bridges as the North Pond and South Pond. In 1903 a monument to the Civil War’s Ninth Regiment was added, as well as a playground, ball field and ‘comfort station’. Ice skating was introduced in 1906 by closing the tidal basin’s harbor-water intake pipe for the winter, as called for in Mitchell’s 1891 plan.

In 1939 an additional outcropping was created just south of the park to construct New Haven’s first sewage treatment plant (where the Sound School’s newest building is now located). This caused sediment to build up against the seawall along Park Road, blocking the pipe that kept water flowing in and out of the duck pond at each change of tide. Thus by 1950 the pond had almost no water.

Today a portion of the 1937 stone seawall, which replaced the 1890s wooden bulkhead, still can be seen at the end of the present basketball court along Fifth St. and, on the opposite side of Interstate 95, a remnant of the harbor drive (“Park Road”) along another remnant of the seawall, remains between the Boulevard sewage pumping station and the newer part of the Sound School campus. Unfortunately, in 1902 a concrete company was built between Howard and Greenwich Aves., directly across from Bay View Park—the first of several assaults on Mitchell’s landscaped masterpiece—and the great hurricane of Sept. 21, 1938 destroyed most of the park’s original trees. Despite the park’s official name “Bay View” (often misspelled “Bayview”), residents long referred to it as “City Point Park”.

The City Point School & A New Name for the ‘Point’

In the 1858 New Haven Directory is found the first listing for the Oyster Point School on Howard Ave.: a one-room schoolhouse constructed to accommodate 34 pupils, on a lot purchased by the New Haven City School District from Gerard Hallock on Feb. 6, 1858. In the 1866 Directory it is then listed as the City Point School “at the foot of Howard Avenue” and, in the 1870-71 edition, at 20 Howard Ave. (the property which today is numbered 44 Howard).

This seems to be the first municipal use of the name City Point as an alternate to Oyster Point. The 1877 New Haven Directory lists this as one of the Washington District schools, along with the new Greenwich Ave. School which was built in 1877 at the corner of Greenwich & First St., where Galvin Park is now located. The 1877 Annual Report of the Board of Education states that the “City Point and Washington Branch Schools continued through the Fall and Winter Terms, and then became part of Greenwich Av. School, which was opened May 7th, 1877.”

It perhaps is no coincidence that this first official use of the name City Point in 1866 took place the same year that Gerard Hallock died. The November 1867 map of building lots owned by Hallock’s heirs was filed with the Town Clerk on Jan. 24, 1868, and approved by the Court of Common Council (predecessor of the Board of Aldermen) on May 4 of that same year. It is this author’s theory that the name City Point was coined by Hallock at least as far back as 1840. The name subsequently was promoted by his heirs as a marketing device to tout their building lots as a new fashionable suburban development and to dissociate it from the aesthetically unappealing oyster industry. Changing the original proposed name of City Point’s exquisitely landscaped 1890s park from Oyster Point Reserve to Bay View Park undoubtedly was part of this attempt to upscale the neighborhood’s image.

The 1870-71 New Haven Directory lists Second Street as being in City Point, and Greenwich Ave. as extending from Kimberly Ave. to City Point (i.e. to Sea St.). South Water St. is described as being in Oyster Point, while the City Point School is described as being at No. 20 Howard Ave. in City Point. Thus, by 1870 the names Oyster Point and City Point were being used interchangeably. And, as we already have noted, the neighborhood’s 1875 church chose the name City Point Mission.

By the 1890s the name City Point began to replace Oyster Point as the preferred name of the neighborhood. The 1893 Town and City Atlas of the State of Connecticut contains one of the first accurate, rather than “projected”, New Haven maps to use the name City Point in place of Oyster Point. The map found in the front of the New Haven Directory of that same year has the name “Oyster Point” just off the shore of South Water Street, and the name “City Point” next to Bay View Park, where the sewer pipe emptying into the harbor lay. It was not until 1926 that the New Haven Directory map used the name City Point in place of Oyster Point, while the U.S. Board of Geographical Names did not officially recognize the “new” name City Point until 1939!

By the turn of the 20th century the old name Oyster Point came to be regarded as a derogatory reference to the area. Deteriorating docks of the declining oyster industry along South Water St., the putrid untreated sewage pouring into the harbor from a pipe now covered by the new City Point pier at Sea & South Water Streets, and the foul smell of the city dump that once stood near the corner of Sea St. and Greenwich Ave. dominated the scene. During the Great Depression an impromptu shanty town for the homeless appeared at the dump.

The shore of South Water St, showing decayed docks of former oyster companies. Photo taken in mid 1970s by New Haven Redevelopment Agency.

City Point Yacht Club

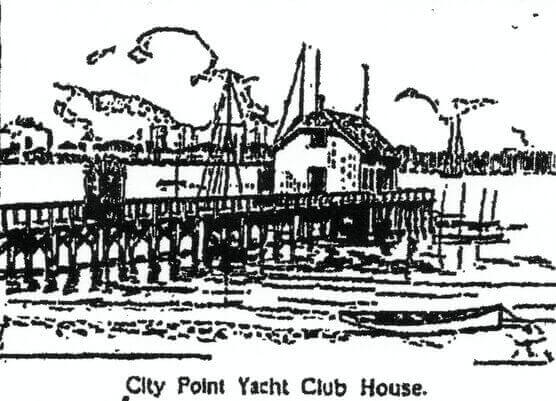

The City Point Yacht Club was founded in 1895. According to an Aug. 30, 1895 report in The New Haven Evening Register, the club’s first activity was to construct a wharf, extending 300 feet off the shore of Hallock Ave (between First and Second St), then purchase a “box boat”. The plan was to sink this boat at the end of the wharf, to provide a foundation for a new clubhouse.

Only four years later the Yacht Club already was making plans for a new wharf down the street, extending off the shore of Hallock Ave near Third Street, behind a lot purchased by the club in 1899: Nº 163[-169] Hallock Ave. In 1900 this had been completed and the clubhouse floated down to the new wharf. By this time the club had grown to about 100 members “with a fleet of 75 boats”.

Today, if you enter 165 Hallock Ave, New Haven CT into Google Maps https://www.google.com/maps/ or simply go here http://bit.ly/2vTTPC3 and zoom into the satellite view, you’ll see the now-empty lot that used to be 163/169 Hallock Ave—formerly site of a house owned by the yacht club. The club’s 300-foot long dock, with the clubhouse at its end, extended into the harbor behind what is now a modern house next to the vacant lot: Nº 165 Hallock Ave. You also can see what that portion of the harbor is today: the rear parking lot of Jordan Furniture! Remarkably, the parking lot still follows the original curving contour of the former harbor shoreline that used to run behind these Hallock Avenue properties, which you can see in the 1934 Aerial Photo.

From Country Village to Urban Neighborhood

Up until World War I, City Point was like a little country village unto itself. A dramatic increase in automobile ownership in the 1920s caused City Point to lose its quiet insular quality. Nevertheless, a remarkable number of barns and carriage houses survive in City Point, reminders of its pre-automotive era, e.g. behind nos. 393 & 133 Greenwich Ave., 196 Hallock Ave., 154 Howard Ave. (which once housed the neighborhood’s first Stanley Steamer automobile) & 297 Howard (an unusual brick version whose original owner was a brick mason), 57 S. Water St., and nos. 40 & 74 Sea Street (the latter, recently restored from near-collapse, perhaps being the neighborhood’s most flamboyant). Beside 98 South Water St. stands the neighborhood’s sole surviving oyster barn, where oysters were processed for shipping.

In 1919 this quiet suburban neighborhood’s tranquility was further broken with the construction of the Seamless Rubber Co. factory (now One Long Wharf) on Hallock Ave. This entailed additional filling to extend the shore, so as to accommodate the new factory. While the factory did provide highly valued jobs for many City Point residents over many decades, the chemical waste which the factory regularly dumped into the harbor contributed to the harbor’s growing pollution.

The Vanishing Point & Lost Identity

By 1888 plans were made to extend the Boulevard to Sea Street and to drain the West River salt marsh behind Greenwich Ave., where Kimberly Field (formerly called St. Peter’s Oval or simply The Oval) now stands. Thus the intersection of Sea St. & Greenwich Ave. no longer would be covered by high tide twice a day. The 1911 New Haven Atlas shows this as having been completed, and the marsh land as being privately owned by Clark, Goodrich, Logan, Steven, and St. Peter Church. However, by this time only the area behind Greenwich Ave. from Second to Third Streets actually had been drained. This allowed for the extension of Second St. to Kimberly Ave. in 1906 and the construction of the Kimberly Ave. School that same year, the construction of St. Peter School in 1911, and the construction of a new street—St. Peter Ave.—in 1918.

Residents growing up in City Point in the 1920s to the 1970s recall that the Boulevard stopped North of the rail road tracks (even though the city directory beginning in 1895 describes the Boulevard as extending from Whalley Ave. to Sea St.). To travel from Kimberly Ave. to the Boulevard one had to walk across the Grant Street Bridge: an elevated foot bridge built in 1907 that began at the end of Grant St. and crossed over the rail road cut to Morris Street.

Between Kimberly Ave. and Sea St. there was only a large sewer pipe which residents used as a foot bridge to cross the West River salt marsh. The appended map of sewer lines in the back of the 1911 New Haven Atlas shows this pipe crossing the salt marsh, with the water extending northward between Kimberly & Greenwich just past Third St. The map in the 1920 city directory shows a planned road here, but the area still under water.

In 1929 the mouth of the West River was dredged (eliminating the island that required two bridges to cross from Kimberly Ave. into West Haven), and the dredged material was used to fill the remainder of the West River salt marsh behind Greenwich Ave. from Third St. to Sea St., and to create a dirt road between Sea St. and Kimberly Ave. Although officially considered a continuation of the Boulevard (even though a bridge extending the Boulevard over the rail road tracks was not built until 1978), residents referred to this dirt road between Kimberly Ave. & Sea St. as Dump Road due to the dump that immediately developed along the shore here. By the mid-1930s the area between Kimberly Ave. and Greenwich Ave. finally had drained sufficiently to create the athletic field that sits there today.

More significantly—with the water on the western side of City Point now gone—City Point was no longer a “point”!

Unfortunately, zoning regulations and wetlands conservation laws, which would have prevented such environmental disasters, did not yet exist. Perhaps to appease residents over the loss of the salt marsh, the city used fire hoses to flood the field every winter for many years so that it could be used for ice skating.

This drainage of the salt marsh (called The Mud Flats by residents) also allowed for the 1931 construction of the second Saint Peter Church on Kimberly Ave. (which replaced the original 1903 church, now Brams Hall of the Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School), primarily to serve the area’s rapidly growing Irish Catholic population. In 1901 the new parish’s northern boundary was declared to be the rail road cut, with many of its members living not only within the traditional Hallock Ave—Greenwich Ave—South Water Street borders of City Point, but also within the Kimberly Ave. area. With City Point’s western border now less distinct, some residents of Kimberly Ave., Grant St., Plymouth St. and Cassius St. began to think of themselves as being City Point residents, particularly during the 1920s through the ’60s—even though these streets never were part of the geographic “point” from which City Point had derived its name, nor were these streets part of the Hallock family’s 1868 housing development known as City Point. (Nevertheless this area—as well as Spireworth Village aka Trowbridge Square—was part of what had been referred to as the Oyster Point Quarter during much of the 19th century). Thus it was during this era that City Point was defined by some residents as being “south of the rail road tracks”. One even can trace the blurring of City Point’s boundaries back to the late 1870s when Greenwich Ave. was extended an extra block beyond the Point and Hallock property, from Kimberly Ave. to Lamberton St., thereby creating one side of Kimberly Square (which, despite its name, is a triangle—not a square!).

At about this same time, the construction of the present railroad station on Union Ave. caused many residents gradually to redefine the Hill neighborhood. The Hill (once known as Sodom Hill and later Mount Pleasant) originally had derived its name from the upward slope along Congress Ave., beginning at the now-extinct West Creek (where Route 34/The Oak Street Connector now is located), and was separated from the Oyster Point Quarter by a branch of West Creek that ran just North of, and parallel to Columbus Ave. (This later would be drained to create the Derby Rail Road cut.) The Hill’s other original boundaries included West St./Winthrop Ave. (or later, the West River) on the west, Oak St./Morocco St. (now Legion Ave.) on the north, and Hill St. (now Church St. South) on the east. With the completion of the present rail road station in 1919, many residents began to define the Hill as comprising all of the area radiating from the upward slope of Union Ave.—and therefore incorporating the City Point neighborhood.

For many residents this initiated the gradual loss of City Point’s distinct neighborhood identity.

During the Great Depression and the rationing of World War II many homeowners simply did not have the money to maintain their properties. As a result, many of the lovely old homes in City Point and nearby neighborhoods began to deteriorate. Lack of tax revenues during this time did not allow the city to provide basic services such as street repairs. Urban decay had set in. After World War II the federal government gave returning veterans low interest mortgages with very low down payments to purchase housing. However, the mortgages only could be used to purchase a new, not pre-existing, home. Simultaneously the government began a massive highway construction program, while spending virtually nothing on rail roads and other mass-transit systems. New Haven’s own deteriorated trolley system shut down in 1948. The decline of the rail road soon followed, and by the 1970s New Haven’s train station was in total disrepair. Ill-conceived urban renewal programs during the 1950s and ’60s razed entire neighborhoods, with no provisions having been made for the displaced residents and businesses. At this same time unscrupulous real estate agents engaged in the now-illegal practice of “block busting”: white home-owners were contacted and told that “coloreds” were moving into the neighborhood, so they had better sell lest their property become worthless.

All of these factors contributed to an explosion of suburban sprawl, with devastating ecological impact. Vast swaths of highway were cut through historic neighborhoods, sucking the economic life-blood out of cities, exacerbating racial and economic divisions in our society, and making our nation—particularly its automobile-oriented suburbs—utterly dependent on foreign oil. With the decimation of New Haven’s neighborhoods, the city was left with Real Property consisting of over 45% tax-exempt properties (mostly institutions such as universities and hospitals that serve predominantly non-residents) and a housing stock that is only c. 30% owner-occupied, thus providing most residents with little incentive to care for neighborhoods which they do not “own”.

The 1949 harbor dredging and back-filling, and the 1950s construction of Interstate 95 (Connecticut Turnpike) completely eliminated the portion of the harbor facing Hallock Avenue:

the final step in the total obliteration of the geographical “point” or narrow peninsula which originally defined City Point.

Bay View Park was split in two and its picturesque duck pond destroyed. Even the City Point Yacht Club, once located on a dock at Hallock Ave. and Third St., was forced to relocate over by the Kimberly Ave. Bridge—and thus is no longer in City Point! In the 1980s condominiums (which due to their gated, insular design, hardly can be considered part of the neighborhood) were built on a former neighborhood beach, which for a time had been the site of the City Point Athletic Club [“ACs”] baseball field. Thus City Point’s once expansive public beaches were reduced to a tiny strip at the end of Howard Ave.: a fragment of Lane’s Shore (named after one of the old oyster companies).

As older residents died or moved away, the collective memories of what defined the City Point neighborhood slowly disappeared, and for many residents the neighborhood soon lost its identity.

By the early 1970s Interstate-95 had become a demarcation of de facto racial segregation in City Point: the area south of the highway was virtually all (non-Hispanic) white, while the portion of City Point north of the highway had become predominantly black and Latino.

This racial segregation contributed to the Completely Inaccurate—but growing illusion—that City Point only consisted of the area south of the highway, while everything north of the highway was “The Hill”.

Thus many City Point residents today—particularly many living in that two-thirds portion of City Point north of Interstate-95—incorrectly think they simply live in “The Hill” or “Hill South”. (“Hill South” is actually a large police district originating from the 1980s, when the four Police Dept. quadrants were replaced with smaller “districts”—including “Hill North” and “Hill South”. These soon expanded into municipal administrative districts, as well. In recent years some have confused these districts with “neighborhoods”: recently the city placed banners throughout the Hill North police district that proclaim “Hill North is my home”!—even though these police districts do not conform to traditional neighborhoods—and indeed are too vast in area to meet any standard definition of the word “neighborhood”. Given the historical tension between minority communities and urban police departments, there is a bizarre irony that such a community would call a police district its “home”!)

In 2001 the one-third of City Point south of Interstate-95 was made a “local historic district”. Purportedly this was to preserve that area’s buildings from further modern alterations. However, New Haven has no effective means to enforce historic district regulations. Consequently, property owners continue to make modern-looking exterior alterations with no penalty and “demolition by neglect” remains endemic in such historic districts. Additionally, New Haven’s Historic District Commission has a lengthy track-record of approving alterations that do not meet The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. Thus, the primary impact of New Haven’s local historic districts has been to artificially inflate real estate values and property taxes, thereby gentrifying such districts. In City Point, the local historic district has reinforced the myth that City Point consists only of the area south of the highway.

Adding to the neighborhood’s loss of identity is the fact that the City Plan Dept. and Police Dept. maps show “The Hill” as encompassing everything from Legion Ave. down to South Water Street: City Point does not officially exist!

New Urbanism

By the late 20th century a national New Urbanism movement took root which promotes the rebirth of city neighborhoods that are pedestrian, mass-transit and shopping-friendly and not automobile-dependent. This gradually has had an impact in City Point. In the 1980s the abandoned, boarded-up houses in the neighborhood were too numerous to count. Today such houses are a rarity in City Point (and usually the temporary result of an unfortunate fire or foreclosure).

Likewise, nearby Kimberly Square, which traditionally served as City Point’s neighboring commercial hub, has undergone a renaissance of its own, even boasting a large, modern supermarket. In 1978 the long-contemplated bridge carrying the [Ella T. Grasso] Boulevard over the rail road tracks finally was constructed and at this time city planners coined the name Kimberly Square Neighborhood, in an effort to revitalize the area. In the early 21st century, St. Peter’s was demolished to make way for construction of the Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School and Second St. was returned to approximately its original 1868 configuration. Thus today residents of Kimberly Ave., Grant St., Plymouth St. and Cassius St. generally consider themselves part of the Kimberly Square Neighborhood or The Hill, rather than City Point, even though those four streets are south of the rail road cut.

There also has been a greater effort in recent years to fill empty lots in the City Point neighborhood with houses that blend better with the surrounding historic buildings. For example, nos. 149 to 165 Hallock Ave. are obviously modern tract homes, but the steep roof pitch with gables facing the street, bright colors, front porches and architectural detailing (typical 19th century practices) make these houses welcome recent additions to the neighborhood.

Additionally in recent years the portion of City Point that lies south of the highway has become more racially and ethnically integrated. For example, in the 2010 property assessment database, 6 of the 13 one-to-three family homes on the section of Greenwich Ave. south of the highway list resident homeowners with Spanish surnames: for one home purchased in 2001, and five purchased in 2006 or later. Thus New Haven residents in general have decreasing reasons to view the south-of-the-highway portion of City Point as an exclusively White Anglo enclave.

EPILOGUE

Unlike a town or ward, a neighborhood is not a legally defined entity with precise boundaries. Thus residents never will agree on what constitutes City Point. The traditional East-West boundaries (Hallock & Greenwich Aves.) are generally uncontested because of the water that once defined these. Indeed, the street grid on modern maps of New Haven still allows one to visualize the narrow “point” that formerly was bounded by these avenues.

On the other hand, the northern boundary always will remain controversial, because the perceived northern boundary of Oyster Point or the Oyster Point Quarter changed over time: from Columbus Ave., to the 1848 rail road cut, to the northern edge of the 1867 map of new building lots, or even—in the opinion of those who know little or nothing of the neighborhood’s actual history—to Interstate 95.

Adding to the controversy is disagreement among residents as to whether City Point should be considered an independent neighborhood or one of several neighborhoods that constitute The Hill (or “Hill South”), i.e. along with Kimberly Square and Trowbridge Square. Considering the historical “migration” southward of City Point’s perceived northern boundary, as well as the fact that Gerard Hallock was instrumental in developing both Trowbridge Square and City Point, perhaps an acceptable compromise would be to describe City Point as “a distinct neighborhood within a larger area that today is called The Hill”.

In stating this compromised definition, this author must point out that the steep rise from the shore of downtown’s long-vanished West Creek north of Congress Ave—a rise from which The Hill derived its name—was long-considered by New Haven residents and cartographers to be a distinct topographical feature—distinct from the steep bluff that formerly marked the Oyster Point Quarter: a steep bank along the southern side of a former creek just north of Columbus Ave, continuing southward along the harbor shore along former West Water Street—parallel to Cedar St. and Hallock Ave—and following the harbor shore down to the end of Oyster Point, where Sea St. & South Water Street now intersect.

But then, it also must be acknowledged that City Point—is no longer a “point”! ~*~*~

>>To see ~ Historic MAPS ~ AND ~Historic Photos~ of the City Point neighborhood, as well as other pages on this website, click MENU on smartphones; on PC scroll back to top of this page and click desired page tab. Continue scrolling downward to read “Sources, With Notes”: materials used by the author to research City Point’s history.

Author Christopher Schaefer, a long-time member of the New Haven Museum And Historical Society, The New Haven Preservation Trust, the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, has lived in City Point in the 1871 Lane-Hubbard House at 84 Second Street since 1986,

and becomes visibly perturbed when told that he lives in a mythical neighborhood called “Hill South”. Despite his proposed compromised definition in the preceding Epilogue, he personally prefers to think of City Point as a separate neighborhood, distinct from the Hill. However, despite rumors to the contrary, he (currently) has no plans to have it declared The Independent Republic Of City Point.

SOURCES, With Notes

Annual Report of the Board of Education of the New Haven City School District, for the year ending September, 1858 New Haven: T.J.Stafford, 1858

Annual Report …City School District, for the year ending Sept. 1, 1868 New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1868 [This is the first municipal report to list the former Oyster Point School as the City Point School– unfortunately with no explanation for the name change.]

Annual Report …City School District, for the year ending Aug. 31, 1877 New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1877

Atlas of the City of New Haven, Connecticut Philadelphia: G. M. Hopkins, 1888

Atwater, Edward, ed. History of the City of New Haven New York: H.W. Munsell & Co., 1887

Baldwin, Simeon Public Parks New Haven: Penderson & Crisand, 1881 [briefly mentions the history of The Cedars beach]

Barber, John W. History and Antiquities of New Haven, Connecticut from Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time…3rd edition. New Haven: Penderson, Crisand & Co., 1870

Benham’s New Haven Directory New Haven: J. H. Benham, 1858-59 [includes first listing of Oyster Point School], 1866-67 [now listed as City Point School], 1870-71, 1875 [The 1870-71 edition lists the City Point School at 20 Howard Ave., near S. Water St., and lists Second St. as being in City Point and Greenwich Ave. as extending from Kimberly Ave. to City Point. The other numbered streets of City Point as well as Hallock Ave. are not listed, since they had not yet been built upon. South Water St. is described as being in Oyster Point. Thus, at this time the names Oyster Point and City Point were being used interchangeably. This also would bolster the claim by some residents that City Point begins on the even-numbered side of Lamberton St., between Hallock & Howard Aves., since this is the northern boundary of the 1867 map of building lots, approved for sale in 1868: the official establishment of the Hallock family’s housing development which they named “City Point”.]

Brown, Elizabeth Mills New Haven: A Guide To Architecture and Urban Design New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976 [gives brief history of some of the houses in New Haven, including City Point]

Caplan, Colin M. A Guide to Historic New Haven, Connecticut Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2007 [guided walking/driving tours for New Haven history buffs; includes history of many City Point houses]

Carroll, J. Halsted Memorial of Gerard Hallock New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1866

http://www.cityofnewhaven.com/CityPlan/pdfs/Maps/NeighborhoodPlanningMaps/Hill.pdf [This City Plan Dept. map of the Hill comprises all of the areas formerly known as Sodom Hill and The Oyster Point Quarter.]

www.census.gov [Both the Kimberly Square and the City Point neighborhoods together comprise New Haven’s 2000 census tract no.1404. The City Plan Department’s copy of this map labels tract 1404 “City Point”, further adding to the traditional confusion and disagreement over what actually constitutes “City Point”. The City Plan Dept.’s version of the census map also points out—quite correctly—that there are no “official” neighborhood boundaries in New Haven.]

City Yearbook of the City of New Haven, 1876 Hartford: Case, Lockwood & Brainard Co.

City Yearbook of the City of New Haven for 1932 New Haven: The S.Z. Field Co., 1933 [This edition includes a brief history of New Haven’s major bridges, and describes the 1929 dredging at the mouth of the West River: the beginning-of-the-end of the West River salt marsh.]

Connecticut State Library Fairchild Aerial Survey 1934

Court of Common Council [predecessor of Board of Aldermen], City of New Haven: Vol. 3, 1822-1833, p. 187 [3rd Sept., 1830; list of new streets in the Oyster Point Quarter: Putnum, Carlisle, Port-see, Columbus, Salem, Cedar, Liberty Sts., plus Spireworth Sq. (later renamed Trowbridge Sq.)] ; Vol. 4, 1833-1840, p. 268 [Nov. 12th, 1839; request to affix numbers to buildings in city so a directory can be compiled]; Vol. 11, p. 111 [May 4, 1868; plan of 1867 map of Hallock’s heirs officially approved for development by the Council]

Dana, Arnold G. The Dana Collection aka New Haven Old and New New Haven Museum and Historical Society [invaluable collection of photos and newspaper clippings from New Haven’s past]

DiChello, Angelo; private photo collection

Doolittle, Amos, engraver Plan of New Haven 1824 [map]

Ernst, Margaret M. Donald Grant Mitchell & the Birth of the New Haven Park System: An Urban Adaptation of Rural Republicanism New Haven: New Haven Colony Historical Society, 1980

Galpin, Virginia M. New Haven’s Oyster Industry: 1638-1987 New Haven Colony Historical Society, 1989

Goldberg, Cary, ed. inside New Haven’s Neighborhoods: A Guide To The City Of New Haven New Haven: George E. Platt Co., 1982 [includes reflections by residents on the racial divide created when City Point was bisected by Interstate 95. Thirty-five years after this book was published, demographic segregation within the neighborhood gradually is dissipating.]

Hallock, Charles The Hallock-Holyoke Pedigree and Collateral Branches in the United States, Being a Revision of the Hallock Ancestry of 1866 prepared by Rev. Wm. A. Hallock, D.D. Amherst: Press of Carpenter & Morehouse, 1906 [“At one time, before the (Civil) war, he was active in the Southern (Church) Aid Society…under whose auspices and furtherance the slaves of the South would have been manumitted without war or bloodshed, as summarily and peacefully as were the slaves of Brazil… It was Mr. Hallock’s efforts to prevent forceful action that brought him to the inquisition of the anti-slavery politicians, who persisted in provoking a conflict, and thereby shortened his life.” According to the death notice in the Hartford Courant, at the time of his death Gerard Hallock was New Haven’s largest landowner.]

Hallock, William H. Life of Gerard Hallock New York: Oakley-Mason & Co., 1869 [his son’s rather defensive biography of his late father, who often was mis-characterized as having been pro-slavery. He in fact purchased the freedom of over 100 southern slaves. Devout Christian pacifist, defender of Constitutional law. Therefore felt “radical” abolitionism, i.e. use of coercion or northern Personal Freedom Laws (which defied federal Fugitive Slave Act) would cause anarchy, civil war and dissolution of Union. He believed—rather naively, we can say today—that the “spread of the Gospel” eventually would result in the end of slavery, so founded the Southern Church Aid Society. His editorials criticizing the Lincoln administration’s unwillingness to negotiate with the South resulted in the Post Office refusing to deliver his New York Journal of Commerce, forcing him to retire to New Haven in 1861.]

Hartley, W. T., surveyor Map of Building Lots in the City of New Haven Belonging to the Heirs of Gerard Hallock, Deceased privately published, 1867 [The rail road continued to own the odd-numbered side of Lamberton St. just across from these new building lots into the 20th century. The city approved the sale of these lots in May of 1868: the official establishment of the neighborhood housing development which the Hallock family called “City Point”]

Hartley & Whitford, surveyors Map of the City of New Haven Philadelphia: Collins & Clark, 1851 [This map clearly shows the original location of “Hallock’s Castle” and West Water St., below the bluff along the harbor’s original western shore. A one-block fragment of West Water St. still survives behind the New Haven Police Headquarters: an obscure reminder of how far north the harbor once extended.]

Hartford Daily Courant September 22, 1874 under News of the State: “Public improvements in New Haven render the removal of the old Gerard Hallock mansion necessary.” [This is when it was moved across the street to the corner of Cedar and Lamberton Sts. It was demolished in 1939.]

Hill, Everett G. A Modern History Of New Haven And Eastern New Haven County 2 vols. New York: S. J. Clark Publishing Co., 1918

Hoose, Shoshana City Point New Haven: Schooner, Inc., c. 1979 [intended for students, includes reflections on City Point by older residents; also documents how I-95 had become a racial barrier by the early 1970s: City Point south of I-95 was nearly all white, City Point north of I-95 had become predominantly black & Hispanic and therefore increasingly considered by many residents to be part of The Hill rather than City Point.]

Howard Avenue Methodist Church Seventy-Fifth Anniversary 1950 [program of worship services and parish history]

Hughes, Arthur H. & Allen S. Morse Connecticut Place Names Hartford: The Connecticut Historical Society, 1976

Land Records, City of New Haven: Vol. 123, p.404 [deed transferring a parcel from G. Hallock to William S. Barnes, Oct. 25, 1847; apparently Barnes was the first oysterman on the point]; Vol. 126, p.415 [deed transferring a portion of the aforementioned parcel to Denison Hall, June 2, 1848]; Vol. 133, p.29 [deed transferring the aforementioned parcel from Hall to Richard W. Law, April 10, 1850; advertisements for Law’s oyster co. state that it was founded in 1847. In an undated newspaper clipping given to this editor, Law’s grandson is quoted as saying the company was founded in 1850.]

Land Records, City of New Haven: Vol. 172, p.37 [deed transferring 50′ X 100′ lot on Howard Ave. in Oyster Point from G. Hallock to The New Haven City School District, Feb. 6, 1858]; Vol. 322, p.280 [deed trasferring the City Point School to Mary Elizabeth Coe (wife of William Coe), Mar. 2, 1878]; Vol. 330, pp.125,352 [lien against Mary Coe for “repairs or remodeling” of “the City Point School House, No. 3 Howard Avenue” for $125.25 due; Nov.5,1878,Jan.25,1879; deeds do not yet assign a number to this property, but directories call it No. 20 Howard Ave.]; Vol. 391, p.67 [$1,600 mortgage with New Haven Savings Bank, Sept. 26, 1887—possibly to transform the old one-room school house into the 1880s-style residential structure that exists today, & likely incorporating at least the foundation of the former school house?]; Vol. 491, p. 98 [additional $5,000 mortgage taken out by Coe, secured by this & two other City Point properties, Sept. 28, 1897]; [author unable to locate deed transferring property from Coe to J.Smith, despite hours spent cross-checking indexes; obstacles include nearly illegible script, similar descriptions of nearby lots, & no street address number on property deeds] Vol. 519, p. 540 [deed transferring ownership from Jeremiah Smith to Nellie Manville, May 11, 1899; Vol. 523, p. 159, Vol. 529, p.404 restore original lot dimensions]; Vol. 663, p. 476 [deed transferring same lot—now described as No. 44 Howard Ave.—from N. Manville to Chauncey L. Wedmore, May 18, 1911; first deed to give this property a street number in its description; house numbering system was changed on Howard Ave. at least once between 1888 & 1911]

Land Records, City of New Haven: Vol. 262, p. 578 [deed transferring ownership of lot bounded by Hallock, Sixth & Howard to David Shelton, Jan. 29, 1872]; Vol. 339, p. 374 [deed transferring church building from D. Shelton to Methodist congregation, Oct. 19, 1880]; Vol. 348, p. 48 [deed transferring lot at Fourth St. & Howard Ave. from David Shelton to Howard Ave. Methodist Episcopal Church, July 15, 1881]

Land Records, City of New Haven: Vol. 380, p. 471, March 3rd, 1886 “The City of New Haven has taken for the definite layout of South Water Street from the Easterly line of Greenwich Avenue extended, to the Southerly line of Sea Street a strip of land sixty feet (60′) wide, or so much of said strip as was not already dedicated to the use of a street from the owners fronting on said strip; namely from…” [The document then names nearly everyone who owned property on South Water Street in 1886. It then refers to Map No. 382 dated Aug. 5th, 1872. The planned extension of Greenwich Ave. from Sea St. to S. Water St., referred to above and shown in the aforementioned map as well as in the 1867 map commissioned by Gerard Hallock’s heirs, never was carried out.]

Lattanzi, Robert M. Oyster Village To Melting Pot: The Hill Section Of New Haven Chester, Conn.: Pattaconk Brook Publ., 2000 [The upward slope from the former West Creek to the “suburbs” caused the area around present-day Congress Ave. to be named “Sodom Hill”, Mount Pleasant” and finally “The Hill”.]

http://magrissoforte.com [another great source (besides The New Haven Museum and Historical Society aka New Haven Colony Historical Society) for historic New Haven photos. This company, under owner Colin Caplan, also does historic property research]

Mitchell, Donald Grant Mitchell Collection aka Donald Grant Mitchell Papers (Mss 140) New Haven Colony Historical Society [includes his notes for developing Oyster Point Reservation/Bay View Park]

New Haven Directory (including West Haven) New Haven: Price & Lee Co., 1876, 1877, 1881, 1882, 1887, 1891, 1893, 1895, 1896, 1899, 1907, 1919 [1891 edition includes one of the first city maps showing the not-yet-named Bay View Park.] Several of the above sources (Brown, Caplan, Lattanzi), as well as the Howard Avenue Methodist Church archives, confirm that the Howard Ave. Methodist Church building originally stood at Howard & Sixth Street, but New Haven directories do not corroborate this, giving only the original S. Water St location, & later the Fourth St. & Howard Ave. location. This likely is because during the church’s temporary location on Sixth St., the parsonage still was located on S. Water St.]

New Haven Evening Register March 28, 1890 Against Alderman Foote. The Fourth Ward Rebellious. [article and letter to editor claiming site below Fifth St for Bay View Park is being purchased merely to profit Alderman Foote]

New Haven Evening Register April 10, 1890 That Fourth Ward Park [Atty Pigott warns that the railroad could seize shoreline along Hallock Ave, between Lamberton and Fifth St, even after city has developed it into a park. Therefore property near railroad should be avoided.]

New Haven Evening Register June 17, 1890 Ask for an Injunction [In arguing for city not to refuse gift from Philip Marett, writer reminds readers that many years earlier the city had turned down a gift of land from Gerard Hallock to create Bay View Park—but then purchased the same land many years later.]

New Haven Evening Register Nov. 18, 1890 The Fourth Ward Park [letter to editor objecting to site purchased for Bay View Park]

New Haven Evening Register Aug. 30, 1895 City Point Yacht Club to Build a Club House Very Soon “the City Point Yacht Club…came into existence a few weeks ago…At present it has about 60 members.”

New Haven Evening Register Oct. 16, 1899 City Point Yacht Club Supper [mentions the club’s recent purchase of a lot on Hallock Avenue “at the foot of Third Street” where the clubhouse soon will be re-located; “there are now nearly 100 members enrolled in the organization.”]

New Haven Evening Register Oct. 19, 1899 City Point Smoker. Oyster Supper Served in Old-Fashioned Style by Yachtsmen “When the work is completed and the new long dock spiled out the club will be accessible at all times, no matter what the tide, to yachts desiring to land.”

New Haven Evening Register Aug. 10, 1900 Social and Personal [section includes brief update about City Point Yacht Club, with sketch of re-located clubhouse on new long dock]

New Haven Preservation Trust & Conn. Historical Commissionn, Anne F. Niles, ed. New Haven Historic Resources Inventory, Phase I: Central New Haven 1982 [This gives the northern boundary of City Point as the rear yards of 20-32 Lamberton, which is inconsistent with the fact that these addresses—originally a single building lot facing Hallock Ave., but later subdivided—are on Hartley’s 1867 map of new building lots. It was shortly after these building lots were drawn up and offered for sale the following year that the name City Point gradually began to displace the name Oyster Point.]

http://nhpt.org/index.php/site/district/trowbridge_square_historic_district/ [a history of Trowbridge Square, one of the three neighborhoods, along with City Point & Kimberly Square, which comprise the old Oyster Point Quarter]

Osterweiss, Rollin G. Three Centuries of New Haven, 1638-1938 New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1953

Patten’s New Haven Directory, for the year 1840 New Haven: James M. Patten, 1840

Petersen, Barbara; private photo collection

Rackliffe, Pamela A. The Origin and Development of the New Haven Parks Designed by Donald Grant Mitchell: The First Three Decades [Masters Thesis] Storrs, Conn.: University of Connecticut, 1987 [The author alternates between spelling City Point’s park as one word “Bayview” or two “Bay View”. D. G. Mitchell’s plans for the park use two words “Bay View”.]

Shumway, Floyd & Richard Hegel New Haven: An Illustrated History Woodland Hills, CA: Windsor Publ. Inc. 1987

Taylor, Joseph: extensive private collection of old photos of New Haven

Townshend, Doris The Streets of New Haven: The Origin of Their Names New Haven Colony Historical Society, 1984

Town and City Atlas of the State of Connecticut Boston: D. H. Hurd & Co., 1893

United States Coast Survey From a survey made for the City of New Haven, Connecticut, Sheet No. 6 [topographical map] New Haven: 1877 [interior of the city executed by the City Engineer’s Office]

Visel, Timothy C. New Haven’s lost natural oyster beds – Account of George McNeil, son of J. P. McNeil of The McNeil Oyster Company paper given at the Sound School, New Haven, June 2010

Warner, Robert Austin New Haven Negroes: A Social History New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1940 [The 1949 dredging of New Haven Harbor & 1950s construction of the Connecticut Turnpike/I-95 buried all but a remnant of the ancient 3/4 mile Long Wharf which once began near the present Knights of Columbus Museum, and was last expanded in 1812 by New Haven’s “Black King” William Lanson, a prominent leader of New Haven’s free black community.]

Withington, Sidney The First Twenty Years of Railroads in Connecticut New Haven: Yale University Press, 1935 [The Derby Rail Road opened on Aug. 8, 1871, but the rail road’s “cut” through New Haven appears on the map in J. W. Barber’s 1870-71 directory, so that portion likely already had been constructed by 1870. Also seewww.TylerCityStation.info re. the Derby Rail Road.]

www.yaleslavery.org [Site includes information on Rev. Simeon Jocelyn who founded nearby Spireworth Village (later called Trowbridge Square) in 1830, where free blacks and whites would live together. When he proposed establishment of country’s first Negro College, a white mob stoned his house. (Northerners generally were opposed to slavery, but did not support equal rights.) In 1833 Connecticut passed “Black Law” outlawing such schools (including Prudence Crandall’s in Canterbury, CT). Law repealed in 1838. In 1850s Gerard Hallock further developed the Trowbridge Square area. Also see www.yale.edu/glc/crandall/index.htm regarding correspondence between Jocelyn and Crandall.]

SUGGESTED READING

Walljasper, Jay The Great Neighborhood Book: A Do-it-yourself Guide to Placemaking New Society Publ., 2007